WITH WIND

Both delicate and fearsome, the traditional Chinese dragon kite embodies a mythical symbol of power. Ai Weiwei unfurls a spectacular contemporary version of this age-old art form inside the New Industries Building. He says that for him, the dragon represents not imperial authority, but personal freedom: “everybody has this power.” The individual kites that make up the dragon’s body carry quotations from activists who have been imprisoned or exiled, including Nelson Mandela, Edward Snowden, and Ai himself.

Scattered around the room are other kites decorated with stylized renderings of birds and flowers. These natural forms allude to a stark human reality: many are icons for nations with records of restricting their citizens’ human rights and civil liberties.

Ai’s studio collaborated with Chinese artisans to produce the handmade kites, reviving a craft that has a diminishing presence in China. By confining the kites inside a building once used for prison labor, the artist suggests powerful contradictions between freedom and restriction, creativity and repression, cultural pride and national shame. He also offers a poetic response to the layered nature of Alcatraz as a former penitentiary that is now an important bird habitat and a site of thriving gardens.

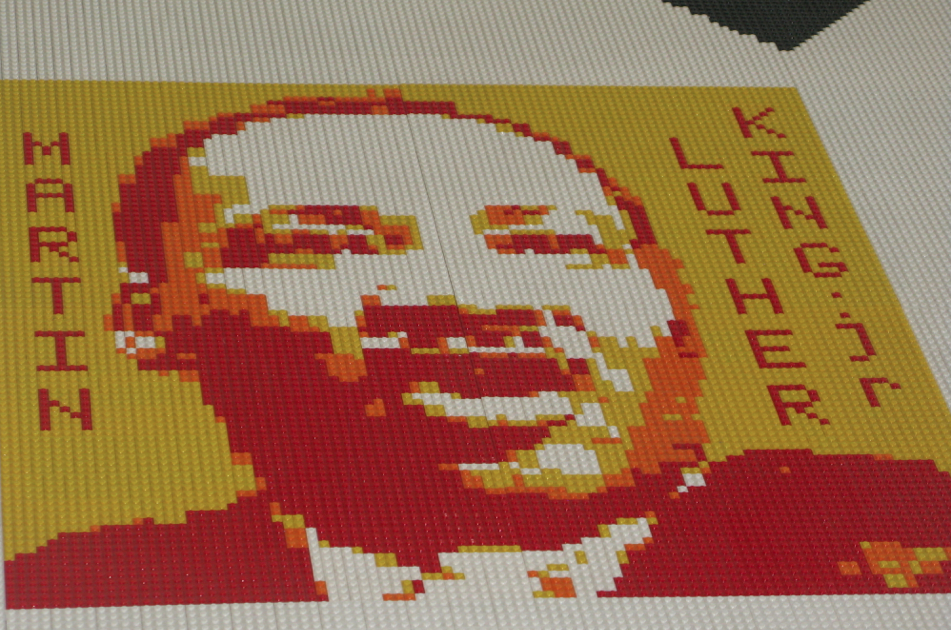

TRACE

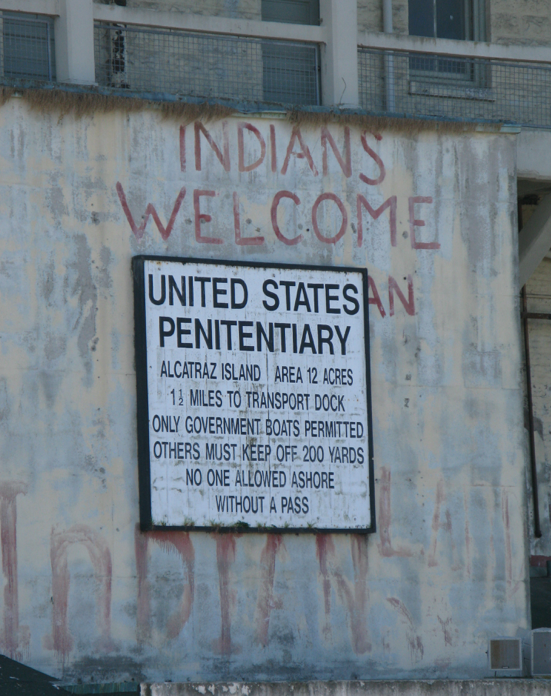

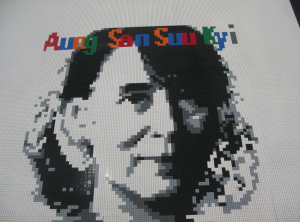

While With Wind uses natural and mythical imagery to reference the global reality of political detainment, this installation at the rear of the New Industries Building gives that reality a human face — or many individual faces. The viewer is confronted with a field of colorful images laid out flat across the expanse of the floor: portraits of 176 people from around the world who have been imprisoned or exiled because of their beliefs or affiliations, most of whom were still incarcerated at the time the artwork was made. Ai Weiwei has called them “heroes of our time.” If the sheer number of individuals represented is overwhelming, the impression is compounded by the intricacy of the work’s construction: each image was built by hand from LEGO bricks. (Some portions of the artwork were assembled in the artist’s studio, while others were fabricated to the artist’s specifications by more than 80 volunteers in San Francisco.) Assembling a multitude of small parts into a vast and complex whole, the work may bring to mind the relationship between the individual and the collective, a central dynamic in any society and a particularly charged one in contemporary China.

See designs for the portraits and learn about the people represented below, or download a guide to the artwork (PDF). Ai Weiwei selected these individuals based on information provided by Amnesty International and other human rights organizations, as well as independent research by the artist’s studio and the FOR-SITE Foundation. Research was completed in June 2014; the status of some detainees may have changed since that time. For more information about prisoners of conscience, visit the Amnesty International website.

From the New Industries Building’s lower gun gallery, where armed guards once monitored prisoners at work, visitors peer through cracked and rusted windows to glimpse an enormous metal wing on the floor below. Its design is based on close observation of the structure of real birds’ wings, but in place of feathers, the artwork bristles with reflective panels originally used on solar cookers in Tibet, a region that has long struggled under Chinese rule.

Like With Wind on the floor above, this piece uses imagery of flight to evoke the tension between freedom — be it physical, political, or creative — and confinement. The sculpture’s enormous bulk (it weighs more than five tons) and constrained position on the lower floor keep it earthbound, but one might imagine its array of solar panels silently mustering energy, preparing for takeoff.

By requiring visitors to view the work from the gun gallery, the installation implicates visitors in a complex structure of power and control. Following in the footsteps of prison guards, visitors are placed in a position of authority, and yet the narrowness of the space creates a visceral feeling of restriction.

Photo credit Jan Sturmann

STAY TUNED

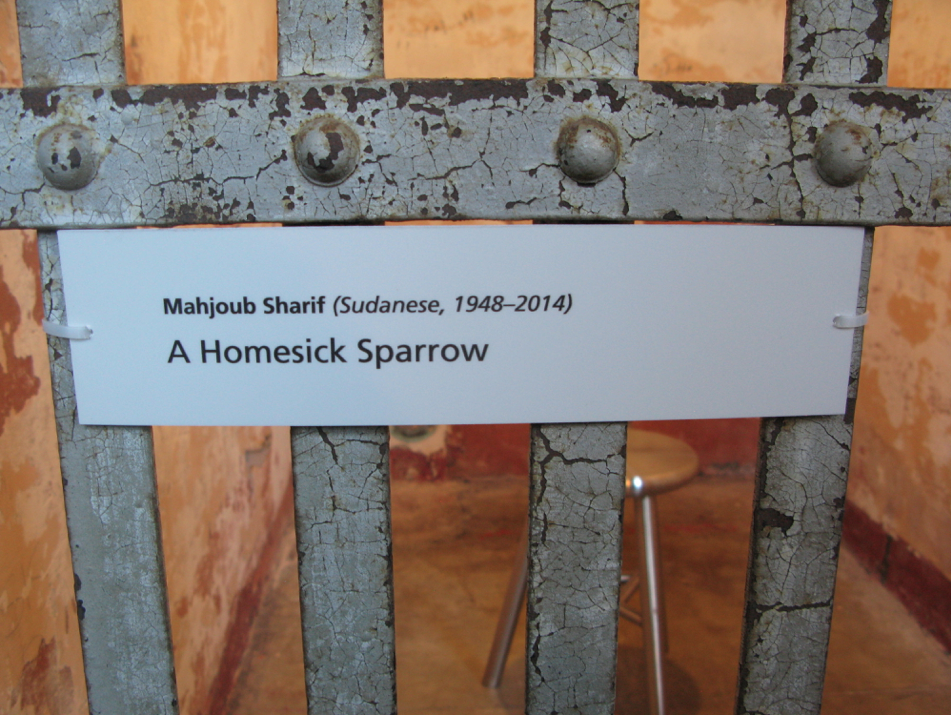

This sound installation occupies a series of twelve cells in A Block. Inside each cell, visitors are invited to sit and listen to spoken words, poetry, and music by people who have been detained for the creative expression of their beliefs, as well as works made under conditions of incarceration. Each cell features a different recording. The diverse selection includes the Tibetan singer Lolo, who has called for his people’s independence from China; the Russian feminist punk band Pussy Riot, opponents of Vladimir Putin’s government; and the Robben Island Singers, activists imprisoned during South Africa’s apartheid era.

Ai Weiwei has described the texture of the individual voice as a particularly potent vehicle for human connection and communication. Heard inside a cell, speech and singing create a powerful contrast to the isolation and enforced silence of imprisonment.

For the full sound experience you can go here to listen to every individual sound recording .

ILLUMINATION

One of the most haunting spaces in the prison — a pair of tiled chambers in the Hospital once used for the isolation and observation of mentally ill inmates — resonates with the sound of Tibetan and Native American chanting in this austere and moving installation. The Tibetan chant is a Buddhist ceremony for the goddess Palden Lhamo, protectress of Tibet; it was recorded at the Namgyal Monastery in Dharamsala, India, a monastery historically associated with the Dalai Lama. The Hopi music comes from a traditional Eagle Dance invoking the bird’s healing powers. Hopi men were among the first prisoners of conscience on Alcatraz, held for refusing to send their children to government boarding schools in the late 19th century. (For information about Hopi prisoners on Alcatraz, visit the National Park Service website.)

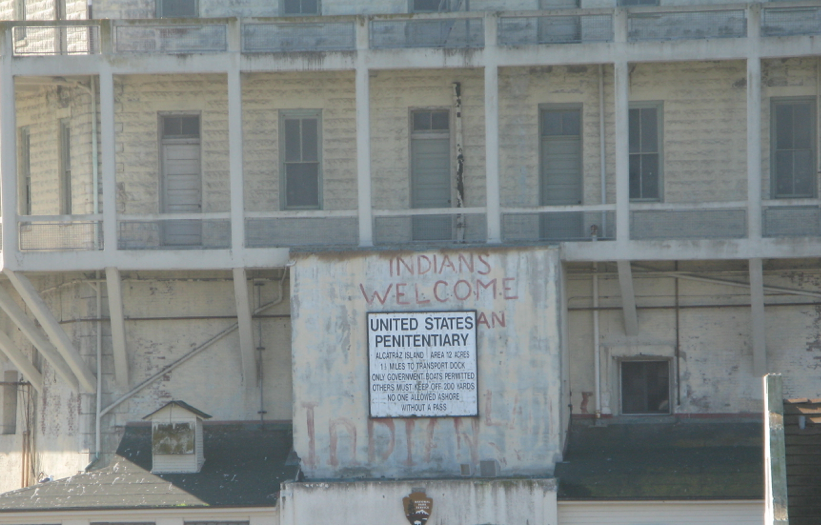

Drawing pointed parallels between China and the United States, the work pays homage to people who have resisted cultural and political repression — whether Tibetan monks, Hopi prisoners, or the Indians of All Tribes who occupied Alcatraz from 1969 to 1971. The placement of the chants in the psychiatric observation rooms suggests an unexpected analogy: like subjugated peoples, those who have been classified as mentally ill have often been dismissed, deprived of rights, confined, and observed. Under the severe circumstances of incarceration, chanting could serve as a source of emotional comfort, spiritual strength, and cultural identity.

You can listen to the sounds here

BLOSSOM

In this work, Ai Weiwei quietly transforms the utilitarian fixtures in several Hospital ward cells and medical offices into delicate porcelain bouquets. The artist has designed intricately detailed encrustations of ceramic flowers to fill the sinks, toilets, and tubs that were once used by hospitalized prisoners.

Like With Wind in the New Industries Building, Blossom draws on and alters natural imagery as well as traditional Chinese arts. Rather than referring to national iconography, however, the flowers here carry other associations. The work could be seen as symbolically offering comfort to the imprisoned, as one would send a bouquet to a hospitalized patient. The profusion of flowers rendered in a cool and brittle material could also be an ironic reference to China’s famous Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956, a brief period of government tolerance for free expression that was immediately followed by a severe crackdown against dissent.

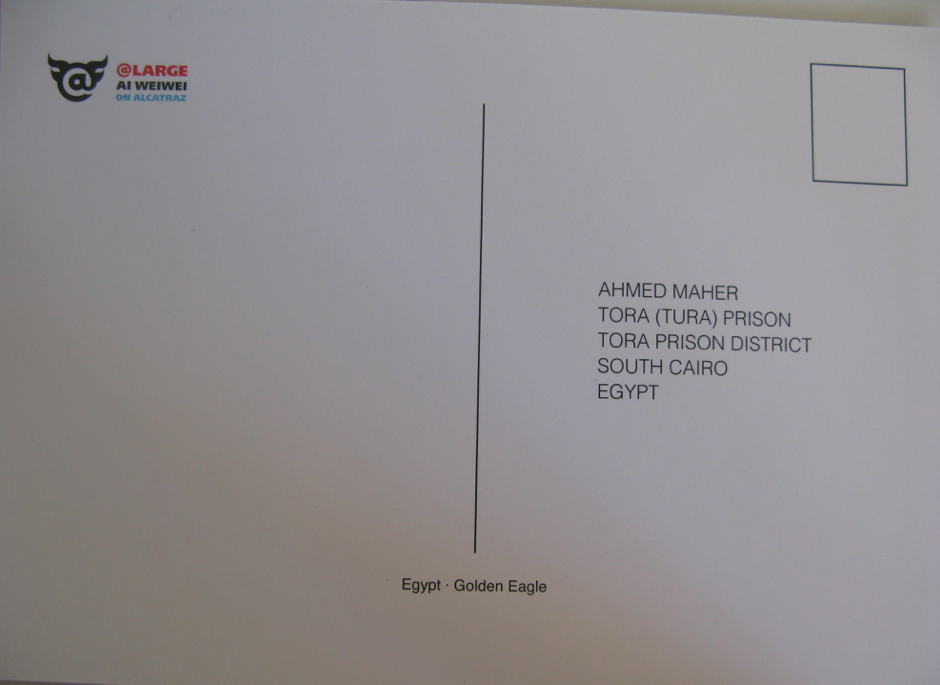

YOURS TRULY

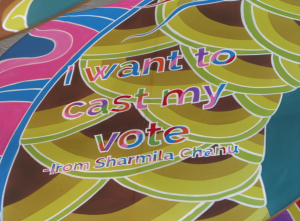

While several other works in the exhibition expand visitors’ awareness of prisoners of conscience around the world, this installation in the Dining Hall offers visitors the opportunity to correspond directly and personally with individual prisoners. Visitors are invited to write postcards addressed to some of the detainees represented in Trace, the series of portraits in the New Industries Building. The postcards are adorned with images of birds and plants from the nations where the prisoners are held. Cards are gathered and mailed by @Large Art Guides.

Ai Weiwei has spoken of the deep feeling of isolation that afflicts incarcerated people. He says that political prisoners often fear that they — and the causes they fought for — have been forgotten by the outside world. This work is a response to those concerns, reminding detainees that they are remembered — and reminding exhibition visitors of the detainees’ individuality and humanity. In the spirit of free expression, visitors may write any message they wish. Yours Truly brings home ideas at the heart of the exhibition: the responsibilities that we all bear as members of a community, and the importance of communication as both a personal expression and a force for social change.

For information about individual prisoners, visit the Trace page or download a guide to the artwork (PDF).

I leave the island of Alcatraz very sad and moved by this show and very thankful for everything I have and specially for the people who lost their freedom so that we could enjoy ours .

Here are some more views of Alcatraz . Haunting . Dramatic . I cannot imagine what It must have felt like for the prisoners to see the city lights of San Francisco across the icy dangerous waters every night , so close and yet so inaccessible .

The Occupation of Alcatraz was an occupation by the group Indians of All Tribes (IAT). The Alcatraz Occupation lasted for nineteen months, starting in November 1969 by the Sioux until June 1971, and was forcibly ended by the US government.

Thank you….

It is very sad

we are so lucky

Beautiful and sad, thank you